Guide:Dynamic audio in visual novels

|

|

This page is community guidance. It was created primarily by FulminisIctus. Please note that guides are general advice written by members of the community, not VNDev Wiki administrators. They might not be relevant or appropriate for your specific situation. Learn more Community contributions are welcome - feel free to add to or change this guide. |

The aim of this guide is to give an overview on how dynamic audio can be used in visual novels. It was originally written as part of a presentation at VN;Conf 2023. I have overhauled the guide in 2025 for its publication on the VNDev Wiki. This is a practically oriented guide to dynamic audio aimed at visual novel developers and audio producers working for visual novels. Most of the information found herein is sourced from my work in the video game industry, guides to audio middleware, observations taken from different games, and a couple of game music study books (see "Sources and Recommended Reading"). The aim of this guide is not to be a scientific article and it wasn't written under the premise that it would be an exhaustive overview of every dynamic audio technique that has been used in video games or visual novels specifically. This document may be updated in the future.

Definition

As I have shown in an article on the terminology surrounding dynamic audio, its definition and the definition of the adjacent terms adaptive audio and interactive audio are convoluted and contradictory.[1] Different composers and scholars define these terms differently and some use them interchangeably. As such, I feel it is necessary for me to explain what I mean when I use the term dynamic audio. I'll use Karen Collins' definition in Game Sound (2008), one of the most widely cited publication on the definition of these terms, as a guideline. She defines dynamic audio as "[a]ny audio designed to be changeable, encompassing both interactive and adaptive audio. Dynamic audio, therefore, is sound that reacts to changes in the gameplay environment and/or in response to a user."[2] I will expand its definition by including variability as a possible feature of dynamic audio.[3] Variability means that aside from changes based on the "gameplay environment and/or in response to a user," a game's audio can also change based on random chance. Also, when using the term dynamic audio, all types of audio are being referenced: music, ambiance, sound effects, and voice acting. In literature the focus is oftentimes music, but other types of audio within a video game can and oftentimes are dynamic as well.

Motivation

My main motivation for writing this article was the release of my horror manga inspired visual novel called Mycorrhiza. One of my main directing goals was making the audio dynamic. When looking for reference visual novels and other people's attempts at implementing more complicated dynamic audio systems into their visual novel, I found barely any examples. Ignoring the simplest type of dynamic audio, audio replacement, there were at most discussions about the use of audio layers. There can be several reasons for this:

- Many visual novels aren't as interactive as other types of games, thus insinuating that dynamic audio doesn't play as big of a role in visual novels.

- Bigger, well-known visual novel productions don't make heavy use of dynamic audio, which leads to there not being many role models.

- Indie developers might not be able to easily find experienced audio producers and programmers that can work with dynamic audio.

- Many indie visual novel directors might not know what dynamic audio is, as they might perceive it subconsciously instead of consciously when playing other types of games.

- There aren't many guides about the use of dynamic audio in visual novels out there.

The exact rationale can vary from developer to developer. The combination of reasons 1–3 might result in the notion that trying to use dynamic audio in visual novels is more trouble than it's worth. Whether this is true, is something that every game director must decide for themselves on a game-by-game basis. I am certain there are cases where implementing dynamic audio into a visual novel might not make a huge difference, or where searching for the right staff to make implementing dynamic audio possible is not feasible. I had the advantage of being an audio producer who has experience with dynamic audio and having an awesome and very competent programmer, Alfred, by my side when developing Mycorrhiza. But I would highly recommend at the very least considering whether dynamic audio is something that you might want to use in your visual novel. It is my belief that visual novels, despite their oftentimes limited interactivity, can highly profit from the use of dynamic audio. But before explaining the advantages of dynamic audio, I would like to exemplify the different ways dynamic audio can be used in visual novels.

Dynamic audio techniques

Replacing audio

Audio replacement is the simplest type of dynamic audio and one that is used in pretty much all video game productions, including visual novels. Audio replacement means that the game audio changes completely from one distinct audio event to another (like different musical compositions). Examples would be:

- The player sees a romantic scene between the main character and their love interest. They hear romantic music. Suddenly a love rival storms in and is shocked and angered by what they are seeing. The romantic music stops and a new, dramatic music track fades in. The mood has drastically changed and as such, the music change was similarly sudden.

- The main character is sitting in a café, leisurely drinking a drink. In the background you hear people chatting and clanking their dishes. The main character finishes their drink and leaves the café. They enter a calm side street with trees lining the path. It's a windy day and as such you hear wind rustling through the leaves. The café ambiance fades out as the door closes. The ambiance has changed due to the character changing their location.

- The main character is on their way out of town to meet someone on the field near a big oak. They are currently walking on pavement, and you hear the clacking of their shoes on hard rock. The road ends and the character steps into a grassy field. The rock-footstep sound is replaced by the rustling of grass beneath their shoes. Due to the change in floor type, the footstep sound has changed. In less interactive visual novels, where you don't directly control the character, footstep sounds oftentimes take the form of an ambient track (a continuous, looping track that plays in the background without requiring continuous input from the player). Within more interactive or hybrid visual novels, however, this could be an example for dynamic sound effects.

There are several ways to implement this type of audio, as there are many ways in which you can transition from one audio track to another, from an audio track to complete silence or from complete silence to an audio track. Visual representations of the different techniques are added under each section. Marked in red are the trigger points, meaning the moments the game has received the command to change the audio.

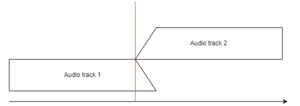

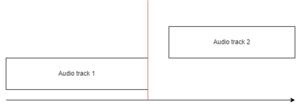

- Sudden stop and/or sudden start. The prior audio track suddenly stops playing or the next audio track suddenly starts playing. Using this technique can feel less seamless but can mirror a sudden changes in mood. It can be advisable to mask the sudden start or stop of an audio track with a sound effect.

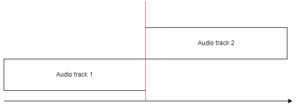

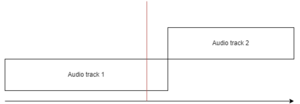

- Fade out and/or fade in. Fading out means that the volume of a track is gradually reduced to zero. Fading in means that the volume of a track is gradually increased from zero to its target loudness (usually a track's full volume). The length of these fades can be set to different values depending on preference and there are different forms of fades, like linear, logarithmic etc.

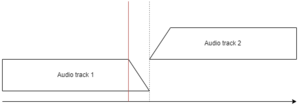

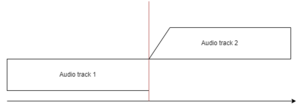

- Crossfade. Crossfades create smooth and pause-less transitions between two tracks. The prior audio track starts fading out while the next audio track is fading in. Long crossfades can make a transition between two tracks more seamless. Note that crossfades can sound jarring if the previous and next track differ too much, such as them being in different keys or them having different tempos. In these cases a long crossfade can make these problems stand out more.

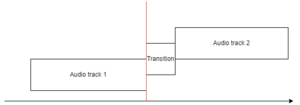

- Transition. A transition is added to the prior audio track as it receives the command to stop playing. This transition is oftentimes a music snippet that is seamlessly added to the stopping piece to conclude it with more finality than a fade could or to transitions into a new piece.

You can also combine these techniques. The prior track can suddenly stop and the following track can fade in, for example. The stop and start of a piece can also be delayed. After a specific action has triggered the audio replacement, the game could wait for a certain amount of time before triggering the audio change. In practice this is oftentimes utilized by waiting until the music has reached the end of a measure before transitioning. There can also be a pause of variable length between the prior audio track stopping and the next audio track starting.

Manipulating audio

Instead of transitioning from one distinct audio track to another, it's also possible to manipulate a singular audio track. One semantic problem is determining when an audio track has been manipulated and not replaced. How different can a piece be before it should be classified as audio replacement? What if it's distorted beyond recognition? What if most of the instrument layers are replaced? This question is difficult to answer and the exact semantics shall not be the topic of this guide. Music, ambiance, and sound effects can be adjusted in a multitude of forms. I will summarize some of the most common ones below and provide examples.

- Pitch. Imagine a moment in a horror game shortly before a monster is revealed. As you read further and further, the music is gradually pitched higher and higher, intensifying the tension and the player's uneasiness more and more. Another example: You have the choice to switch between rooms and there is one specific room with an uneasy atmosphere that you can go in and out of. You could pitch down the music to intensify the uneasy atmosphere without needing to switch to a different track. Once the player leaves the room, the music's pitch returns to normal.

- Speed. Speed changes are oftentimes used to link a character's movement speed to the music. You could have a racing scene in a visual novel where the music gradually speeds up as the main character is described to speed up more and more. Another example could be a scene where two characters are fighting. The more their fight escalates, the faster the music becomes.

- Volume. The manipulation of volume can add to the immersion of a game. Depending on how loud or quiet a sound is, the closer or farther away it seems. A game could have a scene where a character is standing by the side of the road as a parade approaches. The closer the parade is, the louder the parade ambiance becomes. In the case of voice acting the volume of the voice line can be adjusted depending on how close or far away the player is standing from a character. While the main character, a detective, is investigating different rooms, an assistant could be heard complaining in the background at random intervals. Instead of the voice line cutting out as soon as the main character enters an adjacent room, its volume could be decreased to add realism. Another example would be an ending scene. As the character is reflecting on the outcome of the story, the credits' theme becomes louder and louder, symbolizing the approaching ending of the game, until the game finally transitions into the staff roll.

- Panning. Similarly to volume, panning can be a good tool for immersing the player in the in-game space. If a sound source is to the right of the player, then it makes sense to pan the sound to the right and vice versa for the left. To pick up the parade example from above: If the parade is approaching from the right, then it makes sense to start the pan on the right and then pan it further and further into the middle as the parade comes closer and closer. If you were to apply this to the voice acting example above, then you could pan the voice line of the assistant depending on whether the main character has entered a room to the right of the assistant or to the left.

- Manipulation of notes. This is a technique that can be most easily implemented when a music format that is based on musical instructions is used. Examples would be MIDI or MOD. These files aren't prerendered audio files like MP3, OGG or WAV files. Instead, they only contain information about which notes are played when while the sound these notes make is usually provided by the respective sound chip or sound bank. As opposed to prerendered audio files, the musical instructions of MIDI or MOD files can be manipulated. As such, all musical parameters can be adjusted during gameplay, including rhythm, harmony, or melody. An accompanying instrument could seamlessly change into a minor key. Or the melody another instrument is playing could seamlessly change its rhythm. MIDI and MOD aren't commonly used anymore, even if they provide many advantages when it comes to creating dynamic audio. One practical example could be a scene where the mood is rather positive. The sun is shining, and the main character unassumingly makes their way through town. But the further they walk, the more apparent it becomes that something is off. The accompanying piano's cheerful notes are replaced with more and more dissonant ones. Finally, the main character realizes that they haven't seen another human being since leaving their house. They're all alone in this town. The piano accompaniment has gradually changed into a dissonant mess, intensifying the main character's confusion and the terror of their realization.

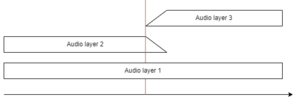

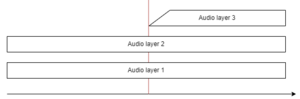

Vertical change. Audio layer 2 is replaced by audio layer 3.

Vertical change. Audio layer 3 is added on top of the already playing layers. - Vertical change. This concept is also called vertical re-orchestration or layering (among a multitude of other terms). Vertical change refers to audio layers (singular instruments or multiple instruments bundled together) being added, removed, or replaced. To give you an example: The main character is presented with three choices regarding which of their friends they would like to hang out with. Each of the characters has their own main instrument that they are associated with. The first character's instrument is for example a piano, the second character's is an acoustic guitar, while the third one's is a trumpet. The general melody-less hang-out music is playing in the background while the player is mulling over the choice. Once they have chosen a character, a melody is added on top of the already playing background music. The melody is played by a different instrument depending on which character they have chosen. This gives each of the character's hang-out sessions a personal flavor while still signaling that this is a general hang-out session. Another example would be a scene where the characters are about to get into a fight. Tense music starts playing while they are throwing insults at each other. Then someone throws the first punch and drums set in alongside the already playing tense music, adding even more intensity to this scene. Music layers are oftentimes synced to each other. One technique that's usually used in this context is starting all audio layers at the same time but setting the volume of layers that aren't needed to zero. Their volume is then increased once they are needed. Alternatively, one could sync the new layer to the timestamp of the currently playing layer. But they don't necessarily always need to be synced. Ambient music or ambient sounds could be examples where this is not necessary. A strong wind sound setting in over the currently playing bird chirps doesn't need to be synced to the bird chirps. Ambient music layers without any continuous rhythmic components also usually don't need to be synced.

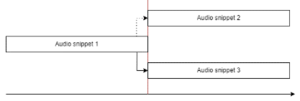

Horizontal change. Audio snippet 1 could potentially jump to snippets 2 and 3. - Horizontal change. Also called horizontal resequencing. The distinction between audio replacement and manipulation is not clear when it comes to horizontal change. Horizontal change generally encompasses audio replacement. If an audio track transitions to another section within the same audio track or an alternative version of the same composition, however, then it could be defined as audio manipulation making use of the horizontal change technique. For the sake of this guide, the following explanation will focus on the transition from one version of a composition to another version of the same composition. A hypothetical scenario could be: The main character is presented with the choice of which attraction they would like to visit at a town fair, a haunted house or a café. Depending on which choice is picked, the music seamlessly transitions into another variation of the track. In practice, this oftentimes means that the transition happens on the beat and the new variation of the track starts where the last one ended. If the original track ended at the end of bar 8, then the new track starts playing at the beginning of bar 9.

- Various other effects/audio signal processing. Audio signals can be processed in a multitude of ways. Examples are reverb, equalization (meaning that the volume of chosen frequencies is increased or decreased by a specified amount), echo, etc. The intensity of the effect can be manipulated dependent on the context. As a character is progressing further and further into a cave, for example, the echo of the audio could increase to mirror the location change. Or a music's high frequencies could be cut as soon as a character leaves a club. The low frequencies of the music still pierce the walls of the club while the high frequencies fade away before they can reach the character's ears, thus adding realism.

Similarly to audio replacement, the audio manipulation can be delayed and there can be a pause before the change. Note that you can also combine several of these and, for example, trigger an echo together with vertical change or manipulate notes while changing the volume. Additionally, you don't have to apply these different techniques to the whole audio track. You can manipulate the pitch, speed, panning etc. of a single layer while leaving the rest of the instrument layers the same.

Interacting with audio

What sets this type of audio apart from other types of audio is that a game developer has implemented the audio in a way that motivates a player to trigger or change the audio. Triggering audio events leads to some sort of reward, lets the player progress through the game, or is the purpose of an area or a specific object. An example for the latter would be a piano standing in the corner of a room that, when interacted with, lets the player play notes by pressing the piano's keys. While this might not let the player progress through the game or reward them, it is still the purpose of this object to let the player consciously trigger audio. This type of audio can employ the same audio manipulation techniques that you have seen above. A player might have to use a slider to manipulate the pitch or the speed of a music track to match it to the pitch or speed of a reference track to progress. Or they might be able to interact with instruments or instrumentalists, which triggers a new instrument layer to appear or disappear. Another technique is giving the player the ability to trigger individual musical notes to solve a note sequence puzzle, for example. Another example: The main character is an up-and-coming violinist studying at a music school who is supposed to rehearse increasingly difficult pieces for concerts. The player can be integrated into this process by making them learn the first few notes of each piece by heart. At each concert, they then must recall the correct order of notes to progress or to be rewarded. Played in succession, those notes form a melody that is either correct or incorrect. Yet another example: The player is a conductor who is at that moment conducting a small ensemble. At specific points they are presented with the choice which instrument is going to join in next, meaning which instrument layer will start playing next.

Chance based audio

Audio can not only change following the input of a player or changes in the environment, but also by chance. One element of chance-based audio are random containers. A metaphorical container could contain multiple variations of an audio event, for example five different footstep sounds. Each time a player takes a step, a footstep sound effect would play. Reusing the same footsteps sound effect over and over would get repetitive quickly. In real life, footsteps don't sound exactly the same. Instead of using only one sound effect, it makes more sense to randomly choose from a selection of slightly different sounds. Another example would be using multiple random containers over the course of an ambient track. Instead of reusing the same bird chirping sounds at the same timestamps, they could be randomized to add more variety. Similarly, a music track could also contain a random container. Each time the track loops back to the beginning, the instrument that plays the melody could be selected at random. You can apply different rules to control how the random audio tracks are triggered:

- When can audio reappear? A common rule is that audio within a container can't appear twice in succession. Hearing the same footstep sound back-to-back, for example, may sound unnatural. You could have it only reappear after one or more other sound effects variants have played. Another common case is that a sound effect can only reappear after all other sound effects in a container have been played. This means that each sound effect is essentially removed from the random container after it has been played until the container is empty and all sound effects are added back in again. This could result in the sequence: 1-4-2-3-5; refill container; 5-1-4-3-2 etc. (this is just an example to help visualize how this could work. How it is handled in-engine doesn't matter as long as it has the same effect).

- How high is the individual chance that a specific sound is played? This is also oftentimes called "weight". You could make it so that "bird chirp 5" has a 40% chance of playing instead of 20%. That way the play chance distribution would be 15-15-15-15-40. Bird chirp sound 5 will thus be heard more often.

- Which audio track can be chosen? You could exert control over the possible choices. There might be 5 different audio layer variants in total, but depending on which conditions are met, different layers are allowed to be chosen. A player might have to trigger a certain event or collect a certain item for layers 4 and 5 to unlock. Before the player has met that condition only layers 1–3 may be randomly selected. Alternatively, after triggering an event only layers 4 and 5 may be selected and layers 1–3 are removed from the pool of possible options.

Additionally, all audio changes presented under "Replacing Audio" or "Manipulating Audio" can be a result of random chance. A piece of music could be horizontally rearranged at random instead of being based on the player's behavior. Or the pitch of a sound effect could be randomized to add variety etc.

The purpose of dynamic audio

The following arguments will also apply to video games in general. What I want to argue is that even less interactive game types like visual novels can highly profit from making use of more complicated dynamic audio systems outside of simple audio replacement.

- Seamlessness and immersion. Audio replacement, even if using crossfades or other types of transitions, can sometimes make the interchange between states feel sudden. Using dynamic audio techniques like adding or removing layers without changing a music piece's basic makeup can feel more seamless. This doesn't mean that sudden changes or less seamless transitions are always undesired. But being able to construct seamless transitions when necessary can make the experience less jarring for the player. Sudden audio changes that aren't justified by what's happening in-game can decrease a player's immersion, especially if a lot of these changes happen in quick succession. Making the player able to interact with audio and thus giving them another means of influencing the game world with their actions, is another factor that can enhance a player's immersion.

- Variability. Especially when making use of chance-based audio techniques, the audio might end up feeling less repetitive and more organic or realistic. A player is less likely to get bored from hearing the same two minutes on loop. Variability also adds to the above-mentioned factor of immersion: Players are less likely to have their immersion broken by unrealistic audio events like the same footstep sound being heard in succession or hearing the same bird chirp sound after a fixed time interval.

- Relaying information. Any audio change can relay information. The simplest version of this is audio replacement. A change in setting or a change in the mood completely replaces the audio. When, for example, the "wandering around town" theme stops and the "sitting inside a bar" theme starts playing, this accompanies the game's changed state sonically. The information provided is: You are now in a different environment. This information transfer can be designed to be more subtle by making use of audio manipulation. One could fade in an extra layer when a new character appears in the bar, for example, instead of changing the music outright. Instead of the relayed information being "I am in a bar but now the focus is fully on this character and the setting is secondary" (if the music were simply replaced), it is now "this character is an additional factor and now I and this character are both in this bar".

- Intensifying emotions. Aside from relaying the information that a specific scene is supposed to be a sad scene, for example, audio generally also tries to evoke or enhance these emotions within the player. This again can be done less seamlessly with the use of audio replacement or more subtly with the use of audio manipulation. Imagine someone dying in the main character's arms. A sad solo piano track is playing during this scene. They say their farewells and then the character passes away. The moment they pass away a solo violin starts playing a heart-wrenching melody, intensifying these emotions. Alternatively, imagine a battle scene where the instrumentation ramps up as soon as the leader of the enemy faction appears, intensifying the scene without outright changing the whole battle track.

Practical example: Mycorrhiza

Throughout this document, I have given you theoretical examples, using made-up scenarios. In this section, I would like to provide you with a practical example: Mycorrhiza. Mycorrhiza is a game where we have made extensive use of audio manipulation and chance-based audio. Let me again thank our programmer Alfred for his work, as the implementation of these techniques would not have been possible without him. The game consists of three different stories, each being behind one of the three doors that are visible on the title screen. Whenever I reference a specific story throughout this section, I will refer to the story's door, meaning the first story is called door one, the second story door two, and the third story door three. If you want to hear a specific audio technique in action, you can do so by playing through the story behind that respective door. You can experience many of the techniques described here in the free demo: https://fulminisictus.itch.io/mycorrhiza

Volume and panning

There are several points within the game where volume and panning are manipulated to create a sense of space. At the beginning of the second door, Scott, the game's main character, starts picking up laughter from a distance. Scott is still far away from the sound source, as such it is quieter at first and panned to the left. The purpose of the panning is to make it clear that Scott wasn't directly walking toward the laughter. Instead, he incidentally walked close to the source while wandering around town. The closer Scott gets to it, the louder the laughter becomes. Once he is standing right behind the crowd, the panning of the laughter is centered fully, and its volume is maximized. A similar example can be found further within the second door inside an apartment complex. He hears someone downstairs and walks toward the sound source. As he is descending the stairs, he hears a relatively quiet stabbing sound to his right. It's coming from an apartment that's a bit further down the hallway. Once he steps closer, the sound becomes louder and is panned further to the right as his right ear gets closer to the sound source relative to his left. Once he turns to the right and looks into the apartment, the volume is maximized and the sound is panned to the middle, as the sound source is now directly in front of him. Both examples serve the function of immersing the player into the game's space and making it easier for them to feel like they are experiencing it from the point of view of Scott. Another use of panning can be found within the third door if the first room is visited for the third time. You can hear a scratching sound but are unsure of its source. There is, however, a definite point on the game screen's x-axis where the sound is coming from. If your mouse is to the right of the sound source, the sound is panned to the left and vice versa. You can thus deduce that the sound source is the left wall. Visiting the room for the fourth time will reveal monsters coming out of said wall. The function of this use of panning was thus to foreshadow where the threat is coming from. It provides information. This can be classified as providing the player with a means to interact with the audio, as the player is encouraged to consciously affect how the sound is panned.

Vertical change

Vertical change is frequently used within the first door. The scary buildup music consists of six different ambient layers and two drum layers that are mixed and matched to the situation. Throughout the first door, there are several scenes where Scott finds himself in a creepy situation with the intensity of said situation increasing the further the scene goes on. When he looks into a dark alleyway, for example, creepy ambiance starts up. Once his eyes fall on the plants that cause animals and humans to transform, another creepy layer is added. Another example can be heard when Scott creeps down the stairs toward the basement inside someone's house. One creepy layer starts up at around that moment. Once a character with a crazed smile on his face fades into view, another creepy layer is added. The most obvious use of this technique is towards the end of the first door when Scott runs away and finds himself on a grassy field. If he stole a journal, then he now has the chance to read it. After each section Scott reads, he stops because he feels like he heard a sound. The player can then choose to continue reading or to stop reading and continue walking. Each time the player decides to continue reading, another creepy music layer is added until, after the third time, the monster that had been chasing him finds and attacks him. The purpose of this technique was on one hand to intensify the scary mood with each added layer. On the other hand, it provides information by implying to the player that the plant from the first example is highly dangerous or that continuing to read the journal in the third example will have dire consequences. Another use of vertical change can be observed at the beginning of the first door when Scott is walking around town. The town track consists of three piano patterns, three drum patterns, and five melodic patterns, one of which is completely silent. All of them have the same length and which one of the piano layers, which one of the drum layers, and which one of the melodic patterns are played is decided at random. This serves the purpose of adding more variety to the track. This track will reappear in the 'horizontal change' and 'chance-based audio' sections, as it is a combination of all three techniques.

Horizontal change

The above-mentioned town theme at the beginning of door one is an example of horizontal change when the layers are observed individually. Instead of them appearing in order (1-2-3-1-2-3 etc.), their order is random. All in all, this serves the purpose of adding more variety to the track. An ambiance-based example similar to the above is the wall-crumble sound used in the building in the second door. It consists of five separate audio files, four of which are different wall-crumble sounds while the fifth one is a silent audio file. The sequence of the wall-crumble sounds is continuously randomized and thus adds to the variety of the ambiance. Another example of horizontal change can be found within door three. In it, Scott can freely choose to explore and revisit four different rooms. Throughout Scott's exploration, he will encounter scary events which will increase a variable called "insanity." Each time the variable increases, the piano chords layer is replaced with an increasingly scary version. At first, the notes played become more dissonant, and later different effects that distort the piano sound are applied. Scott's increasingly deteriorating mental state is expressed through the increasingly dissonant and horrifying music. It also mirrors the player's increasingly affected emotions, intensifying them the further they progress through this story. All in all, there are eight different variations of the piano chords. Whenever the variable increases, the game waits until the end of a certain bar is reached to then seamlessly jump to the next variation. A more seamless version of this could be achieved by using the "Manipulation of Notes" or "Effects" techniques to gradually manipulate the piece. But this was unfortunately not easily possible with the engine we used.

Chance-based audio

The town theme within door one has been explained at length in the above sections. As such this section will be reserved to explaining what the rules of said track are:

- The track always starts the same when it is first triggered: piano pattern 1, melodic pattern 0 (this is the empty audio file), and drum pattern 1.

- Afterward, it randomly decides for each layer, which version will play next and thus decides the next layer combination. It rolls a random number between 1 and 3 for the piano pattern, a random number between 1 and 5 for the melodic pattern, and a number between 1 and 3 for the drums. A possible combination would be 1 for the piano layer, 3 for the melodic pattern, and 2 for the drums. This is a simplified explanation of how this is handled in-engine, as we had to find a good workaround to prevent desync. We made use of "screens" to control each audio layer and Ren'Py's "queue" function to preload each audio snippet into memory. As the aim of this essay is not to give precise instructions on programming these systems but instead to teach you the theoretical aspects of dynamic audio, I'd advise you to either decompile Mycorrhiza to look at its code or to contact me or Alfred if you have any questions.

- The third piano layer, which is higher pitched and more melodic, can't be played twice in succession. The purpose of this layer is to be a contrasting middle section that brings variety before it transitions back to a lower piano layer.

The mentioned wall-crumble sound within the building in door 2, which is randomly horizontally changed, also follows specific rules:

- The same wall-crumble sound can't appear twice in succession.

- The chance for the empty audio container to be played is 50% while the chance for each of the other wall-crumble sounds is 12.5% respectively. This means that there can be longer stretches of silence. This adds to the realism of the ambiance and helps immersion, as it might feel unrealistic to continuously keep hearing wall-crumble sounds without any longer stretches of silence in-between.

Another example that wasn't yet mentioned, is the random SFX containers used in the demo. Within the demo, you can only play through doors one and two while door three is locked. If the player tries to open door three, they will hear a doorknob turning and a thumping sound, signaling that the door is locked. There are three different door-opening-attempt sounds. Each time the door is clicked on, another sound is randomly picked, with the rule being that no sound can be played twice in succession. The same applies to the mouse-clicking sound when Scott is using the computer on the extra screen after having finished the game (not available in the demo). One of three random mouse click sounds is used without the same sound being able to play in succession. This, again, adds variety and realism.

Closing Remarks

Other visual novels have also used dynamic audio techniques outside of audio replacement, though I wasn't able to find many examples and those that I did find mainly made use of vertical rearrangement. Doki Doki Literature Club changes the instrumentation of the piece "Okay Everyone!" depending on whose poem you're currently reading. I'm Just Here to Change the Lights changes the instrumentation depending on which characters are present in the respective scene. Neither technically do so by fading in or out audio layers but instead by switching between different versions of a track. One notable example that lets the player interact with the audio is Alfred's game Usagi Syndrome, which has a piano puzzle. Not having been able to find more examples doesn't mean that they don't exist. But it does imply that more complicated types of dynamic audio in visual novels aren't widely discussed and therefore not easy to find through internet searches or by asking people in the visual novel community. If you know of any more examples of more complicated dynamic audio techniques used in visual novels, then feel free to let me know! I'd love to add a section to this document gathering these examples. All in all, wrote this guide to familiarize visual novel developers with the concept of dynamic audio and give them examples of how dynamic audio can be used. Hopefully, it can inspire you to make use of more complicated dynamic audio systems in your games to enhance your games' effect. Feel free to let me know if you have any questions! My tag on the DevTalk Discord is @fulminisictus.

Recommended reading

- Collins, Karen, Game Sound. An Introduction to the History, Theory, and Practice of Video Game Music and Sound Design, Cambridge 2008.

- Elferen, Isabella van, "Analysing Game Musical Immersion. The ALI Model", in: Ludomusicology. Approaches to Video Game Music, ed. by Michiel Kamp, Tim Summers and Mark Sweeney, Sheffield 2016, S. 32–52.

- Medina-Gray, Elizabeth, "Modularity in Video Game Music", in: Ludomusicology. Approaches to Video Game Music, ed. by Michiel Kamp, Tim Summers and Mark Sweeney, Sheffield and Bristol 2016, S. 53–72.

- Mycorrhiza, Version 1.0 (12.08.2022), Tim Reichert (Director) et. al., WW, PC, 2022, https://fulminisictus.itch.io/mycorrhiza.

- Phillips, Winifred, A Composer's Guide to Game Music, Cambridge 2014.

- Reichert, Tim, "Terminologie veränderbarer (adaptiver, dynamischer, interaktiver) Musik in Videospielen", Ver. 1.0, in: videospielmusikwissenschaft.de, ed. by Forschungsgemeinschaft VideospielMusikWissenschaft, https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:101:1-2023060177, accessed 2026.01.05.

- Sweet, Michael, Writing Interactive Music for Video Games, Upper Saddle River 2015.

References

- ↑ Reichert, Tim, "Terminologie veränderbarer (adaptiver, dynamischer, interaktiver) Musik in Videospielen", Ver. 1.0, in: videospielmusikwissenschaft.de, ed. by Forschungsgemeinschaft VideospielMusikWissenschaft, https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:101:1-2023060177, accessed 2026.01.05.

- ↑ Collins, Karen, Game Sound. An Introduction to the History, Theory, and Practice of Video Game Music and Sound Design, Cambridge 2008., p. 184.

- ↑ You can find also find this addition in: Kaae, Jesper, „Theoretical approaches to composing dynamic music for video games“, in: From Pac-Man to Pop Music. Interactive Audio in Games and New Media, ed. by Karen Collins, Aldershot 2008, pp. 83–84; Schween, Maria, „Entwicklungen der Komposition für Videospiele“, in: Science MashUp. Zukunft der Games, ed. by Gabriele Hooffacker and Benjamin Bigl, Wiesbaden 2020, p. 104.