Guide:Balancing a Game's Loudness

|

|

This page is community guidance. It was created primarily by FulminisIctus. Please note that guides are general advice written by members of the community, not VNDev Wiki administrators. They might not be relevant or appropriate for your specific situation. Learn more Community contributions are welcome - feel free to add to or change this guide. |

The aim of this guide is to provide information on what to look out for when balancing the audio loudness of your game and what techniques you can use to assure that your game is not too loud, nor too quiet. This guide is based on the Visual;Conference talk I gave in 2021. You can watch the full talk here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T6mcdRp0OdM

Intro

The first thing I should note is that when I’m talking about a game’s loudness I mean everything you hear while playing the game, not just the music or any other elements individually.

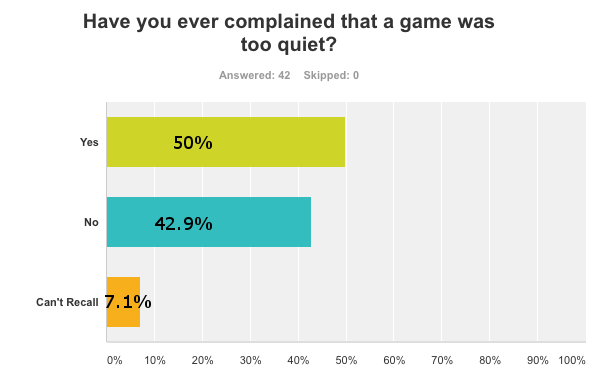

You’ve probably had that experience before: You started a game and the next thing you do is lowering the volume. If not right away, then maybe after a while because your ears are getting tired. These graphs from a questionnaire by Jay Fernandes, a composer and sound designer, indicate that a game being too loud is usually a bigger problem than a game being too quiet.

Figure 1: Results of a questionnaire about game loudness. [1]

The questions that have to be answered to understand game loudness are:

- How is loudness quantified?

- What loudness levels should you aim for?

- How do you measure the loudness of your game?

- How do you adjust the loudness of your game?

- Is it really that straightforward?

How is loudness quantified?

Nowadays the unit of measurement for perceived loudness is "LUFS" (also called LKFS sometimes, which is effectively the same). You might also have heard of "RMS" before, but that one’s rather dated, so it's best to just stick to LUFS. There are several ways to measure LUFS like momentary, short term, and integrated. Integrated is the one that I, just like most articles on this topic, will focus on: It measures the average loudness from the beginning of the measurement period to the end. LUFS is measured in negative units, and the more negative the number is, the lower the loudness is. That means for example, that -14 LUFS is quieter than -12 LUFS.

What loudness levels should you aim for?

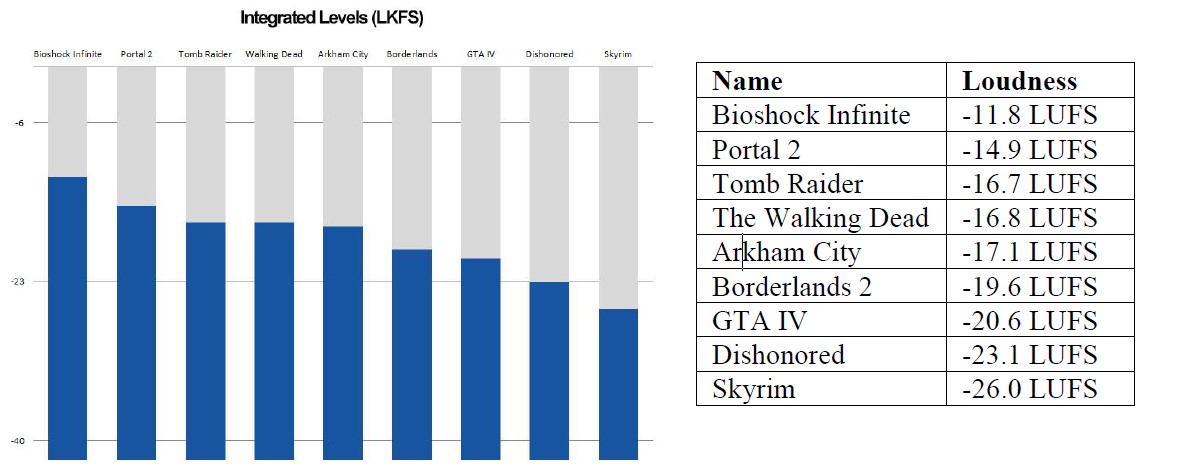

Here’s a big problem: As opposed to television, video games don’t have a set standard. In the case of TV you can get into a lot of trouble for not adhering to the norms. For video games, though, you have way more freedom. Look at this analysis of the loudness of some AAA games by Stephen Schappler, where you can see how big the loudness differences can be. Bioshock Infinite has an average loudness of -12 LUFS while Skyrim has -26 LUFS.

| Game | Loudness |

|---|---|

| Bioshock Infinite | -11.8 LUFS |

| Portal 2 | -14.9 LUFS |

| Tomb Raider | -16.7 LUFS |

| The Walking Dead | -16.8 LUFS |

| Arkham City | -17.1 LUFS |

| Borderlands 2 | -19.6 LUFS |

| GTA IV | -20.6 LUFS |

| Dishonored | -23.1 LUFS |

| Skyrim | 26.0 LUFS |

Figure 2: Loudness in different AAA titles.[2]

For long form broadcast TV content in Europe the standard is -23 LUFS for the whole program[3] and in America it's -24 LUFS for the "Anchor Element" (unless the anchor element cannot be isolated, in which case the whole program needs to be measured).[4] There are also further restrictions in place for ads, like how in America the whole ad has to be measured, similar to Europe’s long form content.[5] But you don’t need to worry about the norm for ads, since a video game would of course fall under long form content.

Here's a definition of Anchor Element from the official American guidelines:

"Anchor Element – The perceptual loudness reference point or element around which other elements are balanced in producing the final mix of the content, or that a reasonable viewer would focus on when setting the volume control."[6]

So, the Anchor Element is the element which a viewer or player would concentrate on the most when setting their volume, which is usually the dialogue. If there’s no dialogue in your game, then in the case of visual novels that might be the music.

Sony, Nintendo and Microsoft, through the Game Audio Network Guild, also recommend -24 LUFS for console games and -16 LUFS for portable games[7] (originally it was -18 LUFS for portable Sony consoles[8]). The value for portable games is higher since they are more likely to be played outside where the ambient noise level is higher. The director at Crytek also noted that they had great experiences with -23 LUFS.[9] As you can see, pretty big players in the industry are stating that they’d like to adapt the TV loudness norms. Note that usually there’s some leeway of about 2 units, so if your computer or console game is -26 LUFS or -22 LUFS loud then that’s not such a big deal. As long as you’re within that -24 LUFS range, you’re adhering to the norm set by the companies mentioned above. If you’re developing for a handheld or mobile game, then you can take a LUFS value of -16 as a reference. The Audio Engineering Society recommends not to go beyond -16 LUFS, and as such it makes sense to scratch the "+" of the ± 2 LUFS grace range that the Game Audio Network Guild recommends for handlhelds.[10]

Aside from loudness there are also recommendations regarding peak levels: They shouldn’t go beyond -1 dB. The peak of an audio file is the highest amplitude of the wave form. If this value goes beyond 0 dB, then this might cause distortion and/or strain on the ears. This is an especially big factor that many game developers overlook, since they don’t necessarily realize that multiple sound sources, like music and SFX and voice acting, stacking up can cause the volume level to go beyond this threshold. The GANG's document doesn’t state anything about a True Peak for mobile and handheld titles but I’d recommend to still stick to a True Peak of -1 dB (1 dB = 1 LU).[11] Fun fact: I found a note about this exact problem in the official SNES Development Manual.[12]

Additionally, a Loudness Range of 15-10 LU is recommended for portable games. This means that the distance between the quietest and loudest parts should be between 10-15 dB/LU. I’m not sure why there is a minimum loudness range, but that’s what the Game Audio Network Guild says.[13] The maximum loudness range makes sense since that way you can make sure that you don’t have many extremely quiet or loud sections. The lack of justification in their document is unfortunate in general, but all the more power to you to stray from their path, if you believe that doing things differently enhances the experience of your game.

How do you measure the loudness of your game?

Before you start measuring your loudness, you’ll have to make sure that you do proper volume balancing of the individual assets first. This includes making sure that the voice lines don’t get drowned out by the music or that the SFX don’t jump scare the player (unless on purpose).

Things start to get more vague from there. I’ve mentioned that Europe would want you to measure the full program while America would want you to measure the loudness of the Anchor Element. Most articles that deal with the topic of loudness in video games shift more towards Europe’s model. Ideally you would measure the loudness of a full playthrough, but since that would be pretty inefficient if your game is long, most say that you should measure the loudness of at the very least half an hour of gameplay, or better yet 1-2 hours to get a more accurate number or even more if you have the time. But not measuring your whole game would mean that you could miss possible peaks that go beyond -1 dB, so be careful. I'd recommend for gameplay snippet or snippets you’re measuring to include quiet and loud scenes in proportion, meaning that if you have a lot of quiet puzzle scenes then your gameplay measurement should feature more of those than loud, action heavy scenes. Note that audio signals below a certain threshold are usually ignored by loudness metering software, so no worries if your game has scenes without any sounds, those will automatically not factored into the average loudness. Since Visual Novels are in many cases more consistent in their loudness than action games anyway, you might not even have to measure for quite as long.

One important thing to note is that you might want to give the players room to increase the volume if necessary. This means that you could measure the loudness while defaulting all volume knobs to 75% or 50%. That way players can still easily turn up the volume beyond the recommended level if they want to. Although I've noticed that this is less of an issue if the game is played on a handheld that has its own volume knob anyway like the Steam Deck or the Switch.

Regarding the tool that you can use to measure the loudness: I recommend Youlean Loudness Meter 2.

- Download the free version of Youlean Loudness Meter 2 and install the application. You won’t need to install the rest.

- Open the software, go to "File"->"Preferences", change the Driver Type to System Audio. Under Output Device you have to choose your audio device.

- Start the game.

- Press the red X at the bottom left ("Clear all measurements") in Youlean Loundess Meter 2 to restart the audio measurements.

- Play the game for a few hours.

- Check the integrated LUFS value and the True Peak Max in Youlean Loudness Meter 2. Additionally, check the loudness range if your game is a portable game.

How do you adjust the loudness of your game?

Now if you’ve found that your LUFS value is actually way higher or lower than what you were aiming for (don’t forget the 2 LUFS grace range), it’s time to adjust the loudness of your audio assets. Just import them into an audio editor and lower/increase the volume of all assets by the same amount. Physics fortunately make this easier than one would think (as long as you’re not using any middleware on your engine that puts effects or a limiter or compressor on the audio). If you lower all audio assets by 1 dB (which is the same as 1 LU), then the loudness of your game drops by 1 LUFS. So if the LUFS of your measured gameplay session is -16 LUFS and you want to drop it down to -23 LUFS, then all you have to do is drop the volume of all audio assets by 7 dB/LU.

If your audio is peaking beyond the threshold of -1 dB but the LUFS is at a good level, then you’ll have to either find out what sound effect or voice line made it go beyond this threshold and lower it or use a compressor on assets that have high peaks to decrease their dynamic range. Personally I’ve heard, though that the -1 dB threshold that is applied to audio assets in general is a bit overkill and that -0.5 dB is good enough as well, but that’s more anecdotal, so it might be safer to try to stick to a true peak maximum of -1 dB.

Is it really that straightforward?

The short answer is no. Loudness isn’t a straightforward topic, neither in music, nor in television, and especially not in videos games.

Games are an interactive medium. Some players will spend more time in louder action sequences while others will spend more time in quiet puzzle sequences. The integrated LUFS value of the play sessions of these different kinds of players will look different. In VNs, though, the variation usually consists of reading speed and choices. These are oftentimes less impactful compared to games with more interaction. But then again: You could have a loud route and a quiet route. Some players will only ever see one of the routes and opinions on whether the game was loud or quiet could differ.

There's also the difference in play session lengths to consider. Measuring the loudness of a whole TV program program meaning either the episode or a whole movie, makes sense because you usually watch them in one sitting. In the case of a game, on the other hand, you have multiple play sessions. So if you have a game that has one longer loud sequence that’s for example 2 hours long and your player starts their play session at exactly that section, then their ears are more likely to get tired after those two hours, as opposed to them starting their play session one hour before that and ending their play session in the middle of the loud section. So some play sessions might seem loud to the player while others will seem fine.

Another problem is the difference between measuring integrated loudness of a full play session and measuring the "Anchor Element". Like I mentioned, most suggest measuring the loudness of a full play session, in television on the other hand some complaints have been brought up against that, which is maybe the reason why American television standards want you to focus on the "Anchor Element". A comedy sitcom series that has little dynamic range and focuses on dialogue will have a more consistent dynamic range, while action series that switch between dialogue and loud explosions will have a bigger dynamic range. This would result in the dialogue of the comedy series being louder than the dialogue of an action series since the loud parts push the LUFS value of said action series upwards.[14] And since understanding the dialogue is pretty important to most, they’ll usually turn up the volume of the action series. So there are also arguments for using the Anchor Element method. There’s a lot of room for experimentation and finding out what’s best for your game. I personally like the Anchor Element option, but it brings its own problems, like deciding what the Anchor Element is or deciding whether all individual Anchor Element items should be equally loud.

Another one would be loudness consistency of individual assets, like making sure that all voice clips are easy to understand or don’t hurt your ears, no matter whether they are whispered or screamed. I don’t have enough time to go into detail on those topics, but these are definitely things to keep in mind as well.

One goal of finding a common loudness level is to make sure that players don’t have to change their volume when switching to another game. Now you might think: "But if I adhere to these tips but the developer of another game doesn’t and the player switches from my game to theirs or the other way around, won’t my game feel too quiet?" Here’s where ear fatigue comes in: If your game is quiet compared to games by developers that haven’t considered their game's loudness then that’s definitely still your win. Having to turn a game up is way less of a painful experience than having to turn it down or to have stop playing after a while. And as mentioned, you can default the volume sliders to 75% or 50% and players can turn them up at will if they want to. Another advantage is that usually audio has to be compressed to reach higher loudness levels, meaning dynamics get squashed and the listening experience possibly suffers.

Outro

To sum things up: Norms work best if all or most people actually stick to them. But even if you’re one of the few people in the VN scene who end up following the tips that I’ve outlined here, you’ll still come out as a winner, seeing how many other advantages having your game be quieter gives you. There’s a lot of uncertainty when it comes to loudness in video games and you might find different solutions that make more sense for your specific game. But hopefully I was able to give you the tools and information necessary to create a good listening experience for your game.

Appendix: Loudness in different VNs

| Name | Time played | Default volume | LUFS | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fate/Stay Night Réalta Nua (Windows) |

2:30 (Prologue Day 1 and Fate route Day 1) | Music: 70% SFX: 90% Voice: 100% |

-12 LUFS | Not featuring OP or OST patch of the Vita version. All voices turned on. Clips heavily (4.1 dB). |

| Palinurus Steam 21.12.2020 |

1:25 | 100% | -15 LUFS | Slight clipping, likely because music was normalized to 0 dB and mp3 compression pushed it up to 0.1 dB. |

| Muv-Luv Extra Steam 21.12.2020 |

2:05 (until 24.10. Wed) | Master 100% Music: 50% SFX: 43% Voice: 90% |

-17.5 LUFS | Opening is -12 LUFS loud (not counted in the gameplay LUFS measurement). Binaural Atmospheric Sounds on. All Voices turned on. Voice over loudness leveling is inconsistent at times (some lines are oddly louder than others). |

| Historia Chapter 1 Ver. 1.0.0 |

1:48 | 100% | -18 LUFS | Staff member noted that it's loud because they showed it at Comiket (which makes sense, since it's a louder environment). Might be advantageous to have one separate version for conventions and a quieter one for PC release. |

| Katawa Shoujo Ver 1.3.1 |

1:35 (until beginning of "Cold War") | 100% | -18.3 LUFS | |

| King of the Cul-De-Sac Ver. 1.0.6 |

~0:25 per run | ~60% | -20 LUFS | Average between three runs. The respective values of each run were: -20 LUFS, -19.5 LUFS and -20.3 LUFS. Was lowered previously because of loudness complaints, according to the developer. |

| One Night, Hot Springs Ver. 1.43 |

0:15/0:28 (two runs) | 100% | -22.5 LUFS | |

| Doki Doki Literature Club Steam 21.12.2020 |

2:30 | ~75% | -23 LUFS | Really consistent at -23 LUFS. No peaking, likely because there are barely any SFX. Dan Salvato noted in an E-Mail exchange that he leveled everything by ear and the (in my opinion) great loudness balancing might be a sign that this loudness range might be naturally good on one's ears. |

| One Night Stand Ver. 2.26 |

~0:12 per run | 100% | -23.5 LUFS | Average between three runs. The respective values for each run were: -24 LUFS, -22.5 LUFS and -24.5 LUFS. Guitar playing (an optional action) raises the LUFS by quite a bit. The game barely has any music. |

| Danganronpa V3 Steam 21.12.2020 |

4:50 (Chapter 1) | 50% | -24.8 LUFS | Japanese voice acting chosen. Interesting that the default volume was that low (compared the other examples above). It's noteworthy that the class trial was louder than the other game parts (shifting the loudness from -25 LUFS up t -24.7 LUFS before dropping again slightly in the chapter epilogue). |

References

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20200220131709/https://www.fernaudio.com/why-loudness-in-games-matters/, archived 2020.02.20, accessed 2026.02.18. The images were unfortunately not archived.

- ↑ http://www.stephenschappler.com/2013/07/26/listening-for-loudness-in-video-games, accessed 2026.02.18

- ↑ https://tech.ebu.ch/docs/r/r128.pdf, p. 3, accessed 2026.02.18

- ↑ https://www.atsc.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/A85-2013-with-Corrigendum-No-1.pdf, p. 16, accessed 2026.02.18

- ↑ https://www.atsc.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/A85-2013-with-Corrigendum-No-1.pdf, p. 71, accessed 2026.02.18

- ↑ https://www.atsc.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/A85-2013-with-Corrigendum-No-1.pdf, p. 62, accessed 2026.02.18

- ↑ https://www.audiogang.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/IESD-Mix-Ref-Levels-v03.02.pdf, accessed 2026.02.18

- ↑ http://gameaudiopodcast.com/ASWG-R001.pdf, unpaginated [page 6/7], accessed 2026.02.18

- ↑ https://www.mcvuk.com/development-news/audio-loudness-for-gaming-the-battle-against-ear-fatigue/, accessed 2026.02.18

- ↑ https://aes2.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/AESTD1004_1_15_10.pdf, p. 2, accessed 2026.02.18

- ↑ https://www.audiogang.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/IESD-Mix-Ref-Levels-v03.02.pdf, accessed 2026.02.18

- ↑ https://bsky.app/profile/fulminisictus.bsky.social/post/3mcrimsuo6k2r, accessed 2026.02.18

- ↑ https://www.audiogang.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/IESD-Mix-Ref-Levels-v03.02.pdf, accessed 2026.02.18

- ↑ https://www.izotope.com/en/learn/the-mixers-guide-to-loudness-for-broadcast, accessed 2026.02.18